Designing a service to help businesses protect themselves

Organisation: Auckland Transport (AT)

Overview

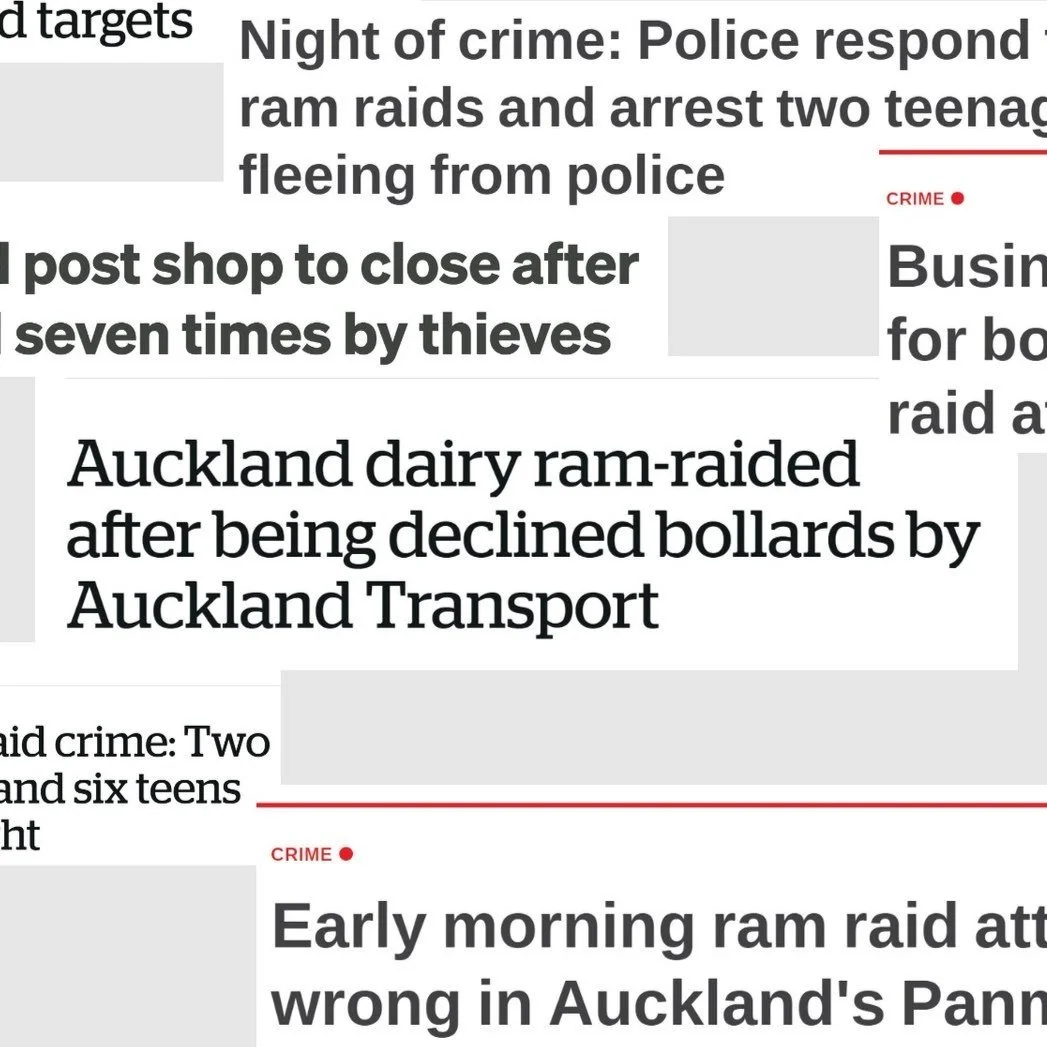

In 2022, Auckland, New Zealand saw a rise in ram raid crimes. This is when someone drives a car into a shop window to break in and steal. Auckland Transport — the local government organisation in charge of transport, roads and footpaths — expected an increase in applications from business owners wanting to install bollards (short posts) to protect their shops.

Media coverage at the time focused on the impact of ram raids on small businesses. Some reports criticised Auckland Transport for not doing enough to help. Under this pressure, Auckland Transport committed to making it quicker and easier to install bollards. The existing process was unclear and involved manual handovers among 5 different internal teams.

I was part of a small Agile transformation team that volunteered to help make this happen.

User need

As a small business owner, I need a simple way to check my eligibility and apply for bollards in front of my shop so I can protect my staff, my peace of mind, and my livelihood from ram raids.

Business need

We need a simpler process for reviewing and approving applications to install bollards so we can keep communities safe, protect our reputation, and ensure bollards are only installed when it’s safe to do so.

Outcome

A new service that lets business owners check if they can install bollards and apply online. This includes joined-up internal processes that reduce the risk of important safety issues being missed.

My role: Service Designer

Key collaborators:

Product Owner

Business Analyst

Graduate Data Analyst

Methods:

User interviews

Insight synthesis

User journey mapping

Stakeholder workshops

Iterative prototyping

User testing

Timeframe: June-September 2022

Approach

User interviews

First we spoke to users who had applied with Auckland Transport to install bollards. I planned interviews to understand their experiences, and coached the team to carry out interviews and synthesise the findings.

We learned there wasn’t much of a process at all. Only a few customers had successfully installed bollards. All were owners of high-end retail shops. They had been passed around multiple organisations and succeeded only through luck, perseverance, and access to resources. One only got through because they knew someone who knew AT’s CEO. This suggested owners of small corner shops would find the process impossible.

“It’s been an absolute nightmare from start to finish.”

“I still wouldn’t know where to start.”

“We’re just trying to make our store as safe as possible.”

“It’s just lucky I knew someone who knew the CEO.”

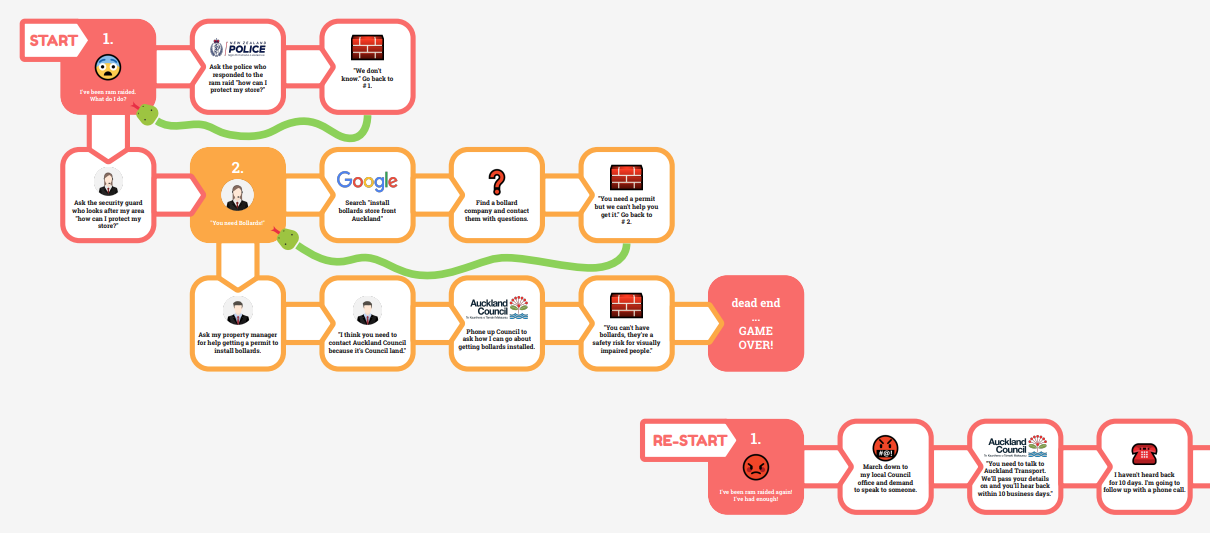

Journey mapping

I used interview findings to create a user journey map. Inspired by board games, I visualised pain points as snakes sending users back several steps, walls blocking their path, and hoops they had to jump through to progress.

It highlighted that:

Neither users nor staff knew how users should to enter the process.

The process was inconsistent and unclear once users entered it.

Many parties could say “no” but it wasn’t clear who could say “yes”.

Success depended on luck, privilege, tenacity, and time.

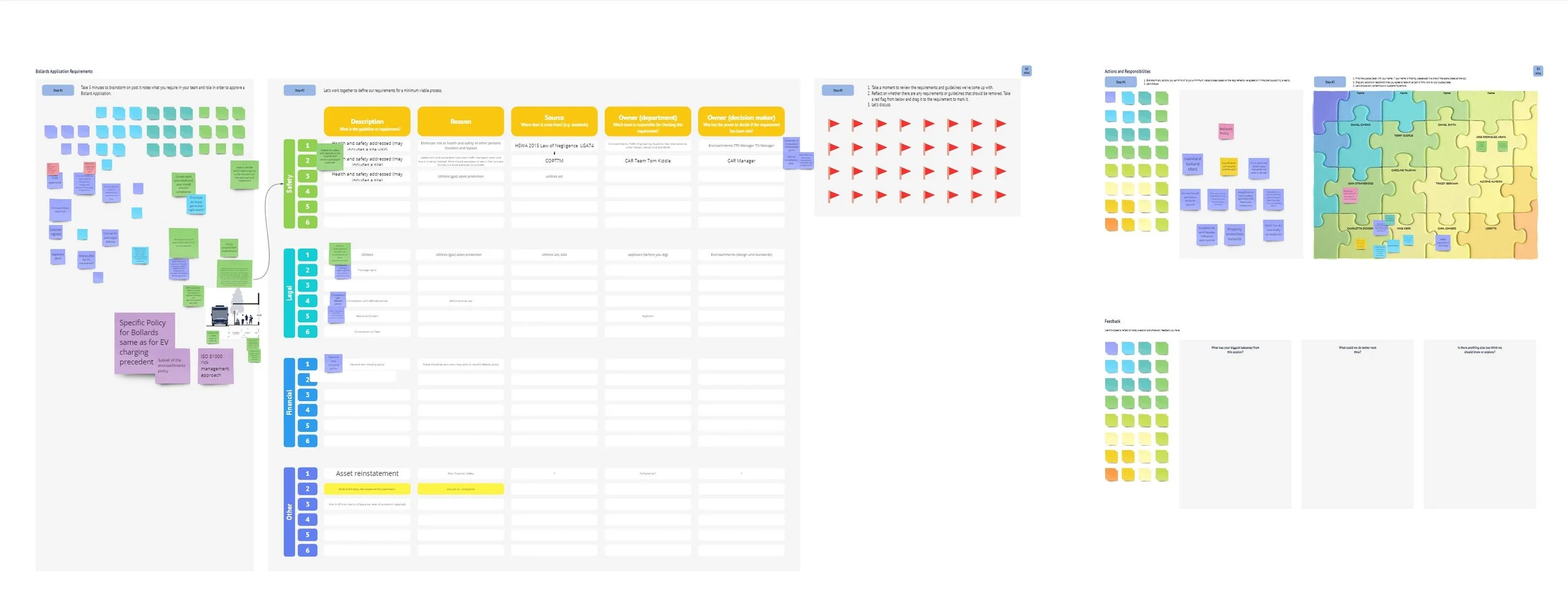

Stakeholder workshop

Next, I designed and facilitated a workshop with stakeholders from 5 internal teams. The purpose was to share user insights and understand each team's role in the application process.

I walked stakeholders through the journey map. By presenting the user experience as a story, I helped them to think beyond their concerns about technical and legal requirements. They were then able to empathise with users’ experiences and opened up to exploring ways to improve the service.

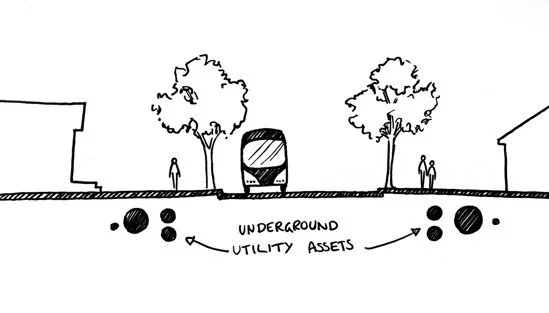

Critical insights

From the workshop we learned that while power cables, water pipes, and gas mains are usually within 500mm of storefronts —the same place bollards must be installed to avoid blocking footpaths— the team responsible for ensuring they are not damaged by roadworks weren't involved in evaluating applications. Damage to underground utilities caused by bollard installation could also harm members of the public. This meant we needed to make checking for underground pipes and cables a mandatory first step in the process.

We also learned:

No team or individual had an end-to-end understanding of the process

Teams worked in silo and handovers were poor to non-existent

Some felt low application numbers made a new process unnecessary, but recognised increased demand would make the process unsustainable

Managing applications was an extra on top of already heavy workloads

Concept testing and iteration

Using our insights we began to create, test, and iterate solutions:

We created a single entry point by setting up a dedicated email address. We managed the inbox ourselves to learn more about user needs by speaking to them. Within two weeks we had 20 applications despite not actively advertising the email address. This proved the lack of applications was, at least in part, due to users not knowing how to apply.

From users’ questions we learned what they needed to know to be able to apply, and used this to create a webpage explaining the process in plain language and directing them to the email.

We iterated the webpage in response to customer feedback. Once we were confident it was right, we created an online application form that fed into AT’s CRM.

Exploring alternative solutions

We learned that AT often has to reject bollard applications due to safety, and accessibility requirements. To avoid leaving sites that were not suitable for bollards vulnerable to crime, we shared our insights with NZ Police and an outdoor furniture supplier they endorsed. I represented AT at cross-agency meetings with NZ Police, Auckland Council and the furniture supplier to share our insights and helpe them explore concrete planters as an alternative to bollards.

Service proposal

To support our user-facing solutions, I led the team to create a proposal for managing the service. This focused on streamlining internal processes and ensuring handovers were smooth. We showed how applications would connect to AT’s CRM and be assigned to each internal team as they moved through the process. We proposed assigning each user a case manager. This would be resourced by the Customer Services team. The case manager would be the main contact for the user and help with any unexpected issues.

Outcomes

Even though shifting organisational priorities after a change in government led to the rejection of the business case for Customer Services to act as case managers, our work means:

Business owners wanting to install bollards outside their shops can easily check their eligibility on the AT website.

Eligible users can apply using a simple online form.

The right team ensures there are no underground pipes and cables that might get damaged before they approve bollards.

Teams can track and manage applications using the CRM. This saves users from navigating messy handovers.

Learnings

What went well?

Agile working

We delivered value quickly and often by testing out ideas alongside discovery. Setting up the email address early made an immediate difference to user experiences while also helping us learn. We built on solutions iteratively to develop the service over time.

Spending time with users

As part of our research, we offered to visit some of the first users who emailed us at their shops. These people were generous with their time and helped us understand their needs. We learned bollards helped them ‘feel’ safe as well as protecting their assets. We used this to build emotional sensitivity into our solutions.

What was difficult?

The pace of local government

To help users find out how to apply, we needed to make changes to AT’s website. The team responsible for the website was busy. They added our request to a long backlog with no clear timeline for completion. To keep things moving, we explained the risks of inaction. We also offered to create simple copy and images ourselves for them to review and approve. We got their buy-in and had the pages live within a week.

Bollards not being enough

We learned early on that bollards don’t always stop ram raids and often can’t be put in place. I found it difficult knowing that improving the process was unlikely to help users as much as I wanted to. We did our best to help users understand the other ways of protecting against ram raids. We also shared our insights with organisations like NZ Police and Auckland Council, who could help in different ways.

Next time I would…

Involve Customer Services earlier

At the start of the project we didn’t see the Customer Services team as stakeholders because they weren’t involved in the process. We only realised they should be when we thought of having case managers support users through the process. They agreed they were the right people to help, but didn’t have the resource required. At this late stage, we had limited time to work together on the business case for resource. In the end, we were unable to build case management into the solution. From this experience I have learned to speak to front facing teams early about any work that involves external users. They are often natural allies for service design and can share valuable insight into user experiences.